The balancing tendency in Adam Štech´s work

Adam Štech has established himself on the Czech artistic scene through so to say naughty painting. Disobedience seems to be one of the main pillars of his poetics. It demonstrates itself through an exemplary inappropriate attitude to the history of arts, namely the chronology of the visual medium,[1] but also in truly unrestrained expression facilitated by his specific attitude to the past that opens up a wide arena for free handling of visual references and legacies of any kind. It is not the mere license of the so-called post-modern unbearable lightness of being that legitimizes recycling and new use of anything and everything available in creation. Above all, it is the author´s outstanding sense for conscious appropriations of historic material in those instances where their updated vision perfectly captures and represents currently ambivalent emotions (baroque, expressionism, cubism, art deco). This cocktail makes his creations distinctive and sovereign.

Štech´s powerful use of colors enhances the drama of forms and visual composition. The author uses colors and forms in two strategic ways – in harmony and in confrontation. Playful personalization of adopted, collaged and transformed formal worlds, typical with their original heterogeneity and incompatibility, is a substantial aspect of his work. There is a reason behind the absurdity of those encounters or of their forceful combination – it is the effort to visually grasp, capture, secure and store authentic emotions that give birth and support, or weaken and extinguish, the identity of an individual. The history of arts is changing while human emotions – positive and negative – remain. In their permanence, they speak through visual gestures of a more distant and recent past.

Contemporary emotion can be expressed in different ways. Štech deliberately avoids pathos. First, he looks for a form or anatomy of emotion in a collage and then he transforms it as a painter, framing it by his own creative personification. The attained expression oscillates between an intimate, often boldly direct representation, and an ironically distant alienation (in kind of a pseudo-modernistic shortcut). Everything is inserted into a searched, often inspired morphology that is not left alone but further shaped, prefabricated, carved and modified in the name of his own internal module.[2] If the Polish sociologist and philosopher Zygmunt Bauman differentiated three Freudian metaphorical modules of denominating those that create society through themselves and their own conduct in relation to utopia at his time – gamekeeper, gardener and hunter,[3] then Štech often unites all three into one contradicting personality, full of dynamic internal movements, high pressure and tension, resembling a volcano right before an eruption.

Figures in Štech´s paintings authentically stem from reality, often having even identifiable physical features. It is the author himself (often using a self-portrait), his friends or dear ones but also those he is trying to circumscribe against, or is forced to draw a line. However, such a personalized foundation allows for tranquil framing of the portrayal of a specific emotion as a vivid, lively situation. All in all, the author´s pictures capture an individual or a group of individuals within a course of events that connects them and freezes them in time and space. The actors are trapped within a contradicting situation. Here, the alchemy of events repaints the features, volumes and often also distinguishable sex of acting worlds.

The essence of those situations consists of interpersonal relations. Constructs of pictures, full of expressive deformations, shortcuts, gestures and eloquently descriptive details are grown from them, modeled by them. Everything is played in a dialectic tension between irony and masquerade on one hand and lethally-poisonous seriousness on the other hand. Štech´s visual expression is characterized by deconstruction of an emotional situation into visual fragments (Self-portrait with a Woman, 2017), into a process of deconstruction and new assemblage of a whole, where the lead is taken by inappropriateness, inaptness, striking coincidences and reversed references that have bulged out as sub consciousness, atop. Those procedures are like a visual surgery, cutting forms and reassembling them into new references to pragmatism, an anatomically-shifted, dreamily-hybrid phantom, by their content. The forms of a human body, face or analogous parts are bended and twisted in similarly mischievous ways into bizarre, elastic new shapes (Těhotná / Pregnant, 2017; Barbora, 2018). The emotions deform bodily parts and human organs, facial expressions and heads to the verge of identifiable integrity. Everything is exaggerated for the sake of a clean expression. This is allusion to designation that has gone off the hands of a fictitious creator. Crashed and pressure-comprised beings are mocking their own pain and suffering, being both pitiful and funny.

The dialectic balancing of contradictions, hand in hand with negation of exactness, is typical for Štech´s attitude to visual narration. If the subject is too romantic, its head must be chopped off in a detail (Žena na skále / Woman on the Rock, 2014). If a motif is too drastic, a relief is offered through the grotesque and a touch of comedy (Fifinka, 2017; Horror / Horror, 2017). The process, linked to a motion and transformation, penetrates into the author´s very subjects. The totality of pregnancy not only transforms a female body but also her psyche, including her partner´s psyche. The picture has a role to capture the whole of this emotional synthesis in its multi-faceted layers and diversity in one spot (Těhotná / Pregnant, 2017; Těhotná Maya / Pregnant Maya, 2017). The transitional state is outlined both through an overall stylization of a figure and references to symbolic attributes (a skull, snake, extremities, clutches, teeth) or through slides into abstract morphology that is an expression of gradual ecstasy, emancipating consciousness from reality (for example Těhotná Maya / Pregnant Maya, 2017). Also the mingling of the masculine and feminine principle while awaiting a new birth expects Štech´s artistic evaluationin the backstage of his studio.

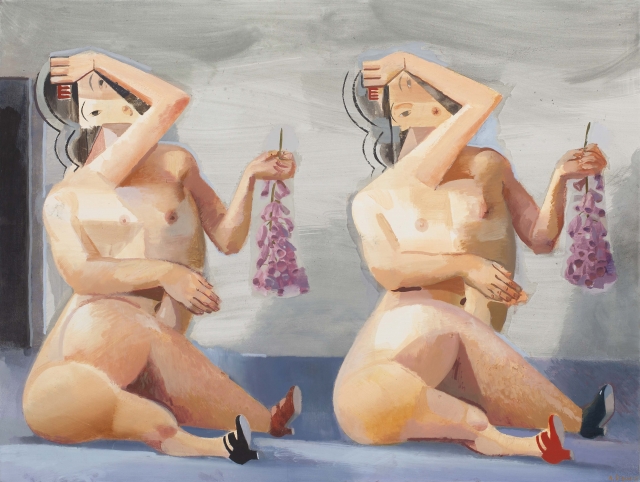

His sense for negation is personified in mental monsters (Agresor / Aggressor, 2017; Predátorka / She Predator, 2017), the formatting of which yet again combines figurative and abstract components (Agresor / Aggressor, 2017; Vanitas, 2018; Abstraktní figura / Abstract Figure, 2018), or updates archaic forms of expression (such as the mosaic in the picture titled Predátorka / Predator, 2017). His works titled Dvojice / Pairs (both 2017) have a peculiar form of humor inserted in them. Female torsos are composed of different styles of painting and techniques (cubism, academism, art deco, painting on china, etc.), which results in a repetitive, irritating phantom of mutated bourgeois style (a bit of a woman, a bit of a pig) that encompasses all of its substantial representative and imitating resources almost in full perfection.

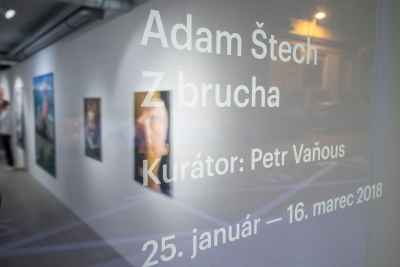

The exhibition titled Z břicha /From the Inside refers to corporality, bound to a transformation of perception and consciousness in a situation that changes standard experience into ecstasy and stylized chaos. There may be a parallel between the shock from delivery with the shock from a hopeless or challenging situation, difficult to resolve, be it in a personal life or creation. Overcoming this anxiety is relaxing and universally liberating. In this stance, the mind and the womb are partners of external irritation and internal shock. As the author says: “The ability to surprise is an important quality of a painting…in this sense, one could say that the rational aspect of a picture should be balanced out by the irrational… that is to say not the art coming from the head but also from the womb.” He further adds: “Our children come from the womb”. They come out from the darkness to the light. And that´s what matters. No more words needed.

Petr Vaňous, Prague – Kutná Hora, January 2018

[1] “I use parts of historic, often reproduced works, in order to create a new context. It is mostly an ironic delimitation against the past, nostalgia and pathos. Thus, references serve rather as traps. My work is mainly based in intuition.” See interview with Štech in: Petr Vaňous (ed.), Motýlí efekt?, Galerie Rudolfinum, Praha 2013, pg. 37. In his older works it was mostly “anachronous interventions into reproduced history and artistic styles”. See also Petr Vaňous, Motýlí efekt? Zákonitosti a nahodilosti současné malby, Prostor Zlín, Vol. XX., No. 2/ 2013, pg. 17.

[2] Compare Petr Vaňous, Vnitřní model naruby, Revolver revue, č. 79/ 2010, pp. 71-84.

[3] When it comes to utopia, Bauman differentiated three types of humans: “If we were to use a metaphor, then the post-modern attitude of a human being towards the world could be compared with the position of a gamekeeper, while the modern attitude could be best characterized by the position of a gardener. (…) . The work of a gamekeeper is based on a conviction that there is order to things if there is no intervention…the gardener (…) believes that there would not be anything like order if it had not been for him and his interventions – the attitude of a gardener (…) is that there would be no order in the world if he were not permanently fighting for it and this attitude now hands over the reins to the hunter. (…). Contrary to a gamekeeper and gardener, the hunter does not care for an overall balance of things, be it natural or artificial. His only mission is to hunt (…),in: Zygmunt Bauman, Liquid Times: Living in an Age of Uncertainty.